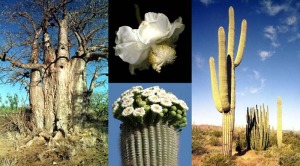

We have been privileged to share years of our lives with both baobabs and saguaros, giant plants that dominate their dry landscapes. The baobab tree (Adansonia digitata) is one of the icons of Africa, with its vast swollen trunk and smooth bark. To St-Exupery’s Little Prince, baobabs were a metaphor for something bad which must be nipped in the bud before it takes over your little planet. In reality, they are magnificent beings which offer bountiful gifts. Their trunks, often hollow, can house bees, barn owls or even people. Their tender leaves are good to eat. Their fleshy white flowers bloom at dusk and offer rich nectar to the bats that pollinate them. Their fruits are useful woody gourds containing nutritious nuts wrapped in a frothy packing rich in Vitamin C, a popular snack for people and wild animals. Their fibrous juicy trunks are used to make string, but are useless as timber. More useful alive than dead, over much of their range they are the only native trees left standing, and they may live for over a thousand years. They are respected and revered; the Tanzanians say “Kila shetani ana mbuyu yake” – every spirit has its own baobab tree.

Half a world away, in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona and northern Mexico, tall saguaro cacti (Carnegiea gigantea) raise massive spiny arms to the sky. A mature saguaro may stand 40-60ft tall with more than 25 arms, and may weigh more than two tons, somehow supported on a base only a foot wide. Inside each stem or arm, a cylinder of vertical woody ribs provides support. The desert people, Tohono O’odham, venerate saguaros and see them as partly human. In spring the saguaros wear beautiful crowns of white flowers, also pollinated by bats. Just before the summer rains, the O’odham and the desert birds harvest their fruits, filled with tiny black seeds in sweet crimson pulp. When we moved to Arizona, one of our O’odham neighbors showed us how to make a long pole from the ribs of a dead saguaro, and knock down the abundant fruits from 30 feet above our heads.

Saguaros grow slowly, usually germinating in the shade of a paloverde or other ‘nurse tree’ where a bird dropped the seed. They may take 10 years to grow 1.5″ high, and can live for up to 200 years. Baobab seeds must be brutalized by passage through an elephant’s jaws and gut in order to germinate. Their seedlings seem to grow best amid dense thickets of other species, where browsing animals can’t reach their tender leaves.

Both saguaros and baobabs have extensive shallow roots, spreading sideways at least as far as the plant is high, and may have a deep tap-root too. When it rains, both plants can rapidly absorb water, then store it for a long time. To conserve water, their leaves are reduced. Saguaros have no leaves at all, photosynthesizing with their waxy green pleated stems. Baobabs produce leaves only during the rains, standing bare for much of the year – but if you scratch that gray or pinkish bark, you will find bright green chlorophyll just beneath it, proving that the “upside-down tree” is not as dead as it looks.

Hug a baobab’s vast trunk – it may take 20 of you to encircle it – and you may feel or hear the wind thrumming through its bare branches. But don’t try hugging the saguaro, just admire it from a distance.