This is a fun extension to Safarizona territory – prompted by our November visit to Kaua’i Island in Hawaii. Chickens weren’t on my to-see list but as we drove out of the airport, there they were, freely roaming the roadsides. During the next week, we met handsome, colourful, confident chickens everywhere – from beach to mountaintops, from suburbs to national parks. Why so many? Who owns them? Who eats them? Their story led us into the much bigger picture of island colonization.

The Hawaiian archipelago was born of fire. As the great Pacific tectonic plate drifted northwest over a ‘hot spot’ or convection plume in Earth’s molten magma, successive volcanoes erupted out of the sea and formed a long chain of islands. The oldest ones, up to 60 million years old, have eroded away and mostly disappeared under the sea. The youngest island, Hawai’i, is currently over the hot spot and still has active volcanoes. Further northwest, Kaua’i is 5 million years old.

The cooling volcanoes were colonized by wandering birds and insects, by seeds borne on wind or ocean currents or in birds’ bellies, and by small animals clinging to rafts of floating vegetation. Lush vegetation grew up, but who would eat it? On islands worldwide, this has played out in different ways. In Galapagos and Aldabra tortoises became the herbivores. Mauritius had giant pigeons, the dodo. Madagascar had lemurs, and New Zealand had 11 giant flightless birds called ‘moa‘, a Polynesian word for any fowl.

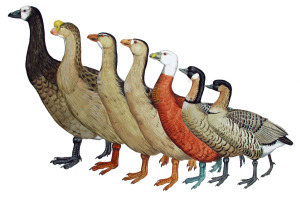

The largest herbivores to reach the Hawaiian islands were ducks, 3.6 million years ago. Lacking predators, they evolved into several flightless forms, some as big as domestic geese. Later, ancestors of today’s nene goose joined them. They became abundant, eating ferns and grass and tree seedlings. At Makauwahi archaeological site, which preserves 10,000 years of remains, we learned that in 300-800 CE, the first Polynesians encountered 7 species of these “moa-nalo” (lost fowls). Unafraid of man, they were soon exterminated. The people brought pigs, which also ate moa-nalo, and chickens, which quickly filled their vacant ecological niche. Moa-nalo were forgotten until archaeologists discovered their bones in the 1980’s.

Enter the chicken! The Asian red jungle fowl, domesticated 8-10,000 years ago, is hardy, tough and eats anything. It is only vulnerable when it nests, on the ground. In all the other Hawaiian islands, sugar farmers introduced mongooses to control the (introduced) rats. But rats are nocturnal, so the diurnal mongooses attacked birds instead, especially ground-nesters; only Kaua’i’s chickens are safe from that threat.

Today the “wild” Kaua’i chickens in parks and reserves are protected. You can harvest chickens that enter your property, but they may be tough. Islanders say: “To cook the moa, boil it in water, with spices and a rock. When the rock is soft, the moa is ready!”

One reply on “Invasion of the Moa”

Your chicken story is of special interest to me cause the one time I was on Kaua’i in a park I saw a group of chickens taking over the benches and picnic tables. It was early in the morning and there were no other human beings around at the time so I was able to take some fun pictures of the chickens and roosters….the kinds of pictures that tell an amusing story. Until reading your story I did not know how those chickens had come to take over that park…..now I know.