If you lived happily in a place for 18 years and had to leave, should you go back? Some say you shouldn’t. But I’ve returned several times to Mangola in northern Tanzania since leaving the home we built and unbuilt. I’ve enjoyed each journey. My visit in January 2020 was no exception.

I had some free days after leading a National Geographic Expedition to Tanzania’s northern parks and I planned to travel to Mangola with some former neighbors, to spend time with them and catch up with other friends from the past. I’d arranged to meet them at an up-market shopping center near the Arusha airport outside of town. While waiting, I browsed the craft shops and a well-stocked, clean supermarket, and sipped an excellent cappuccino by an ornamental pool, where golden-backed weavers wove their intricate nests in the reeds. Such places just didn’t exist 20 years ago.

Soon Chris showed up—a handsome, confident German whose greeting hug always makes me stand on tiptoe—with his feisty Argentinian wife, Nani, beaming up at me. Standing shyly aside was their eldest boy, Kian, now a lanky 18. Chris’s mother, Leonie, ageless and precise, greeted me warmly. She had started our adventure when she first sent us to Mangola 36 years ago.

During our nearly two decades living near Lake Eyasi, this family became dear friends. They lived some distance from us, were also foreigners, and always helpful and welcoming. We all piled into their old Toyota 4WD and headed out along the tarmac highway. As Chris drove, we exchanged news of mutual friends, of their past year, and of my recent safari. We crossed green plains and rolling wooded hills, passed healthy herds of cattle and sheep with their Maasai herders, and stopped at a roadside espresso bar—another surprise—in the market town of Mto wa Mbu.

From there, our smooth paved road climbed the 2000-foot escarpment overlooking Lake Manyara and cut through the Mbulu highlands to Karatu. This road used to be frightful, its gravel and red dirt surface scarred with potholes and corrugations, From dusty mud huts around a muddy market square. Karatu has become a sprawling town with power lines and banks and supermarkets and high-rise buildings.

A few miles past the town, Chris turned left at Njiapanda. We headed down what we used to call the Horrid Road towards Mangola and Lake Eyasi. This unpaved road had been newly graded, and we hummed smoothly along, a dust-cloud chasing us. Gone were the car-swallowing gullies, the cruel staircases of rocks. The long flat section of road, that used to be underwater in years as wet as this one, was now high and dry and flanked by acres of tall maize.

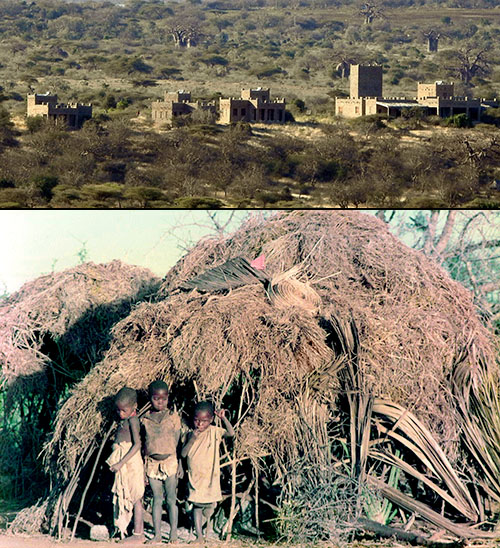

As we swept through our once-primitive village of Gorofani, I saw architect-designed houses, satellite dishes, and power lines. The side road through bush country to the settlement of Kisimangeda looked more familiar, with its rocks and sand-traps. Zooming towards the lakeshore however, I was astounded by the sight of new tourist hotels looking like castles and palaces. Visitors now regularly come to Mangola. They want to see the Hadzabe foragers, see their grass huts, go hunting with bows and arrows.

Maybe add on a visit to the Datoga livestock herders in their black fringed cloaks. Even here, the power poles marched all the way to Kisimangeda Camp, Chris and Nani’s carefully designed tented lodge hidden near the papyrus-rimmed springs. After four decades of diesel generators, my friends would be connected to the grid this week.

Kisimangeda farmhouse peers out from a forest of doum palms and fever-trees. It faces the gleaming expanse of the seasonal lake and the Eyasi rift cliffs beyond.

At the house, Kaunda came by and greeted me: “Shayamo!” “Mtana-ba!” This short, old and endlessly cheerful Hadza man has helped the family in many ways for many years. He has always been their main liaison with his tribe of foragers. He laughs a lot, but his skill with bow and poisoned arrows is legendary, so he is treated with due respect.

For a day I prowled the forest and the lakeshore, finding familiar birds and other wildlife. I climbed the high basalt rock outcrop for a fine panoramic view of the lake. On the next day, Chris let me borrow the Toyota so I could go visiting. My first stop was to visit Ruth, who lives on the ridge between Gorofani and Barazani villages. For several years she’s been building her health clinic there. It is a grand building with white walls and clean, tiled interiors.

Seeing Ruth now reminds me of her 30-year arc from shy schoolgirl to nurse and clinic developer. Her career began in our home not far away. We follow her progress with interest and love. Ruth is now a stout woman in her forties with a calm certainty that any obstacle can be overcome. She greeted me warmly and showed me around the clinic, labs, her home, and guest rooms for visiting medics. It’s still a work in progress, but one day it will be a fine medical center.

What of our old home? I drove back towards Gorofani and turned off by the baobab tree, trying to follow the old track through the Chemchem forest to our place. The bushes had closed in and formed thickets and soon I just had to park and walk. Across the river, diesel pumps throbbed, sending water to the onion fields. Casting around, I stumbled on a new pipeline—a trench cleared and dug through the thickets with a couple of 6” plastic pipes laid in it, to carry water from the springs to new onion plantations on the west side of the river.

Scrambling along that ditch, I managed to reach our old house site. Not much remained. I found a part of the stone wall round our outdoor courtyard and shower and the ruins of a battered concrete couch where our front porch had been. The flamboyant trees we had planted still flourished, overshadowing the baby baobab that will outlast them by centuries. A troop of baboons feasted noisily on the sour pods of a tamarind tree overhanging the rubble of our two-story studio.

We had called our place “Mikwajuni,” meaning “among the tamarind trees”—slow-growing, sturdy, shady, fruit-bearing trees with lovely flowers. I could not see a trace of my office, the first round building we had constructed. But nearby I discovered the concrete lip of my car maintenance pit above the swamp water. This showed that the stream level had risen about 5 feet in 16 years. Most of the tall fig trees and fever trees had drowned and fallen down. New ones were growing up to replace them.

I was happy to learn that the whole Chemchem area of forest, springs, and swamp is now protected by the village. We were part of the struggle to achieve that status and suffered the consequences. As I stood among the thriving vegetation, I could view the ruins of our old home with a strange detachment. We had poured a lot of energy into building it, we had some very good times there. And hard times, too. Our leaving had been traumatic, but we moved on.

I had to move on, too. I drove on to the village and past the mosque, still one of the most elegant buildings in the village with its green and white minaret. Nearby I went to the house of a successful local tour-guide who had been our protegé, enemy, and friend. He was away in Arusha so his lovely wife told me the family news. I learned their daughter is following in dad’s footsteps and going to a tourism college. Near their home, I paid my respects to the grave of Bashki. He had been a powerful chief whose elaborate funeral rites we had attended. Nearby was a small concrete memorial to our mutual friend, Professor Tomikawa, a Japanese gentleman and scholar who had been Bashki’s dear friend.

Continuing through the village, I went to see Athumani and his wife Mama Furaha. These two are now an elderly couple originally from the Usambara mountains near Tanzania’s coast. Athumani, a modest man of great integrity and wisdom, had been the most essential member of our household. He became our trusted guide to village culture. When I arrived near their modest home, I saw Athumani in his white Muslim cap pottering around the goat pen. He turned to see me drive in, recognized me, and he came running over with a warm embrace.

Age had shrunk him and stolen many teeth, but he and Mama looked well. They gave me the news of their nine kids who are scattered around the country. The big news was the wedding of Number Two Son, Bashiri, whom Jeannette had helped deliver. Ever since we left Mangola and gave Athumani all the concrete blocks he could salvage from our home, their new house has been growing next to their sway-backed old mud hut. It is nearly finished, but our friendship continues. I left them with another donation to their building project, and they insisted that I bring “Mama Simba” next time.

Continuing my loop through the village, I passed a small café and spied our former village chairman, Mzee Saidi. He was crouched down, inspecting a drain outside his building. Looking up in surprise he chuckled. “Ho, bwana David! Karibu sana!” he exclaimed and dragged me into a back room for a soda.

Saidi has the impassive face of an ebony sculpture and speaks with the sonorous cadence of a preacher. Saidi had been our supporter and friend when we first came to Mangola. He had invited us to apply for our own plot of land, which led to our building our homestead at Mikwajuni. As usual, he lamented the “worthless people” who had caused us so much trouble long ago. He thanked me for all the positive things we had done for the village.

The sun was getting low as I crossed the main highway to the little shop and café called Gorofani Junction. In the back yard old Mama Ramadhani sat regally in a blue plastic chair. As always, she was surrounded by children, chickens, and goats. She looked up at me in amazement and grasped my hand in both of hers, rumbling a greeting in her deep voice. She is a powerful figure in the village, some say a witch; I say she is a wise friend. Next to her was plump Amina, who had once been one of those cheeky little toddlers and now has contributed two boys of her own to the crowd. Amina’s mother Halima came out and gave me the mandatory flask of hot sweet milky tea. I sat and sipped it, while shy little hands explored the unfamiliar hair on my arms. I watched the sun set behind Mama Rama’s shoulder, feeling warmly accepted by this benevolent matriarchy that seems to perpetuate itself without the visible presence of men.

Try to imagine what kind of story connects these varied characters: an adventurous German settler family, a Hadza hunter, a determined Iraqw nurse, a mercurial Datoga tour guide, an urbane Japanese professor, a respected pastoralist chief, a village politician, a Sancho Panza butler/farmer, and an Iraqw wise woman. We were part of the brew too, a British-American duo of artist/biologist refugees. All of our lives entwined for many years, our diverse spirits drawn together by that bountiful freshwater oasis in an arid Tanzanian landscape.

Why did we live there? What life lessons did we learn from each one of those people? What conflicts did we experience and why did we leave? In our book, Spirited Oasis, we begin to tell that story, and in Beyond the Oasis, we continue it.

© Jeannette Hanby and David Bygott.

6 replies on “Return to Lake Eyasi”

Beautifully written – in word and deed! Your pain, joy and deep connection weave as colorful a tapestry as the Kangas that adorn your friends.

What beautiful kumbukumbu, David. Shukra.

And salamas for Mama Ramadhani, rafiki yangu, aliyenitunza sana.

Glad you liked it. Yes, the old mama is still alive and well, as far as I know. All best!

Hi David, Great hearing about your return to Lake Eyasi. I love how you planned and navigated the village based on your friends’ locations. Presumably you drove back to Kisimangeda after meeting Mama Ramadhani. Kindly include me in your list of people to see in your next visit to Tanzania.

Since I wrote this, I’m sad to say that Kaunda and Saidi have died. They are missed. We are all getting older!

In North Adams, MA is a store named

” ROAM” where I did indeed once inside.

Outside inspecting a book on the use of a piece of cloth ” Kangas : 101 uses” brought me into the travels and photos of your African adventures

Following the breadcrumbs from your

Book on line arriving here in the armchair of Sunday I am again excited with news of one couples travels continuing life long passions

Thank you for welcoming distant less traveled into your experiences