Chapter 5: Kibuyu Partners

Our business relationship and a battle with bureaucracy

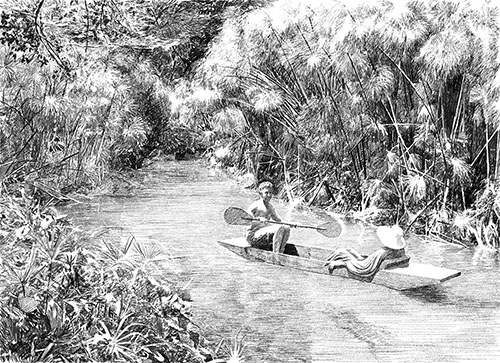

David shoved off from our makeshift dock on the edge of the stream. I almost fell in as he pushed away with a strong pull of the paddle. “Hey, wait for me,” I called as I lunged at the end of the boat.

The punt was a long flat-bottomed boat made for slow streams. David built it by hand, lovingly curving the sides and creating a platform on both ends. Gratefully, I landed on the platform and lowered myself onto one of the damp cushions in the bottom of the boat. Taking the exaggerated pose of a leisured lady, I settled my bonnet on my head and admired David. We’d enjoyed punting during our courtship in England, and I still loved sliding along with my beau stroking the water. I chuckled at the image.

David paddled upstream to a place where the papyrus on both shores hid us from view. We had prepared to fight it out. We had paper and pens, a bottle opener for two beers, and a big sharp knife. Our aim—to agree on a logo and a name for our business. We’d been married for twenty years and had been “in business” together for virtually all that time. Our business and aims in life included learning, educating, and sharing. We wanted to produce things of beauty and importance within our capabilities. To do that, we had to learn to work together.

Two people with disparate styles meant we didn’t find it easy to work as partners. I’m the kind who likes clear plans, pacing, and meeting deadlines. David is much more relaxed about making plans; he considers deadlines as flexible as bungee cords.

And the big sharp knife? Oh, it was for cutting the papyrus stems blocking the river channel. The monkeys and baboons knocked them down to make bridges. Today we needed to work on a bridge between our two minds. For over ten years, we had designed different logos and different letterheads. We could not agree about any. Our little business needed to use stationery that required an official-looking stamp. The government wanted us to register our correct business name so they could tax us properly. Because we’d never reached an agreement, our lawyer had registered us as “David Bygott & Co.”

Yeah, well. Was ol’ “Co.” pleased with being an afterthought, an addendum? Not on yer life, mate. But what could I do about it? Change it, that’s what. But I couldn’t come up with anything better. For the years that I had been the “& Co.,” I endured people telling me how great David Bygott’s work was, when it was at least partly or wholly mine. I was not humble enough to let my spouse and partner get all the credit. I wanted some, too. Besides my creative input, I put in time, lots of it. I also had the emotionally draining, gritting-the-teeth task of pushing and pulling, enticing, and cajoling my partner on every shared project.

David and I have a “rule” about conflicts: whoever cares most about doing something must take responsibility for getting it done. We use a scale of one to ten to determine the intensity of any concern. In this case, I was eight on the ten-point scale; David managed a balanced five. Hence, it was my responsibility to force us to find the right company name together. Our day in the boat was the ultimatum: we had to agree on a name. An added demand was deciding on a symbol, a logo for our business.

We parked the boat in a spot surrounded by a screen of papyrus and listened carefully to the swamp papyrus gossip. Voices let us determine if the illegal distillers were busy in the swamp, snorts told us if hippos lurked in a pool upstream, munching revealed goats or cattle browsing alongside the river, and barks and rustling prepared us to be descended upon by monkeys or baboons. Lucky for us, all seemed quiet, papyrus heads simply muttering in a soft breeze. Sitting in the dappled shade of an overarching fig tree, we engaged our imaginations to search for an image that would represent our business. We designed logos of birds, mammals, flowers, trees, and humble household objects. We agreed on none.

At last, the “aha” moment came: the idea of gourds. Gourds were ubiquitous, in every household, often beautifully carved and decorated. They had multiple uses, for carrying water, milk, beer, and honey as well as seeds and foods.

We drew gourds in various ways, sizes, and positions. And yes, we reached accord on the gourd. Our favorite sketches showed small, rounded gourds (me) and longish, sturdy gourds (David). David added a smart touch by putting paintbrushes, pens, and pencils sticking out of the little gourd.

Delighted with ourselves, we opened the beers, and congratulated each other. Then we just lay down on the cushions and gazed around our outdoor office. Looking up into the leaves of the fig tree above us, we saw the long russet tail of a paradise flycatcher. We heard distant shrieks of hadada ibis and the nearer chatter of lovebirds. They resembled animated green-yellow-red candies clambering among the figs. This was one of those precious moments when we felt in harmony with one another and our precious wild world.

The lovebirds rose like ripe feathered figs and left the tree. We summoned ourselves out of bliss to the business of finding a name for our business. That was easy. Following the image of gourds, came the name, “kibuyu.” Kibuyu is the Swahili word for gourd or calabash and gourds were a recognizable symbol for sharing.

So Kibuyu seemed perfect. I wanted it just that simple. But alas, simplicity is not a hallmark of bureaucracy. The complicated, entangling red tape of bureaucracy trapped us when, months later, we arrived in Dar es Salaam to re-register our business name.

Dar es Salaam is on the Indian Ocean coast of Tanzania, not far south of the equator. The city is a hot and humid place. Some Europeans irreverently call it “Dar es Sal-armpit.” We arrived on a still and sweaty day and found a parking place near the business registration office. There was no shade, but plenty of trash and irritating boys who wanted to guard our car. David fended them off and prepared to defend the vehicle himself.

I put my mind into patience mode, a mental gear between neutral and low range, ready to be stoic or climb hills. I headed into the ugly building. All the offices on the ground floor seemed closed or empty of people. I climbed the stuffy stairs to the first open office. A large woman sat at a table, reading a newspaper.

“Where do I go to register a business?” I asked, after offering my most polite Swahili greetings.

She told me, “This is not the registration office.”

That didn’t answer my question. I switched into low gear.

“Please, can you tell me where I should go to register a company?” I tried once more.

The woman with the carefully braided hair just looked at me. I was in her power. She did not smile. She pointed back out her door and said, “Upstairs.”

I could have used more direction but realized the danger of asking. Upstairs I went. That floor had a big open office. I entered, but no one looked up from his desk.

I greeted the first and friendliest-looking man. “Is this the business registration office?”

“No,” came the minimalist reply.

“Please tell me where I should go.”

He looked me over then pointed back out the door. “Upstairs.”

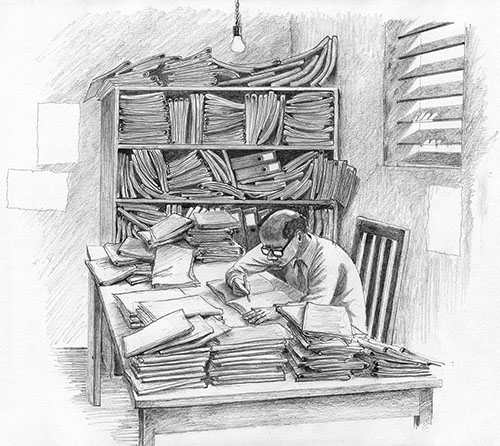

I turned with lips tightened in determination and headed up another squalid flight of stairs, avoiding the shiny, sticky patches. I reached a landing, then another dingy staircase to another floor. All the offices on that level had closed doors. After another flight and another landing, on what I reckoned might be the fourth or fifth floor, I found a large, dimly lighted open plan room, filled to the brim with sweating men. They had acquired the same hue as the piles of damp brown folders around them. I went through my greeting routine again. The man I’d accosted directed me to the back of the office.

In a far corner sat a man at a desk piled high with folders. His bald head faced down towards some papers. He did not look up as I approached. I had time to notice the small dirty window open behind him, letting in some moist air that smelled like moldy fish crates.

I stood and gathered my courage. The man lifted his head. I asked him, in what I hoped was good Swahili, about registering our business under a new name. He looked at me as if I wanted to change the name of the Catholic Church.

“Madam, why do you need to change a perfectly good name to something new?”

“I can’t explain now, but we want to change the name of our business from David Bygott and Co. to Kibuyu.”

He stared at me. “No.”

“Why?” I asked in dismay.

“The name is too short. A business name should have more words.”

I was stupid enough to ask, “Why?” again. David often reminded me not to ask “why” questions, especially not in offices. But the question popped out of my untamed mouth. I couldn’t fathom why a name had to be longer.

He didn’t answer but just said, “Kibuyu…what?”

I stood like a statue trying to think this out. Taking a deep breath, I looked around while the man went back to his papers. The stuffy room was like a crypt, the zombie workers moving slowly, the supplicants bewitched into immobility. Stacks and stacks of wrinkled and wrenched files covered each of the four desks, the one huge table, and many wall shelves. Sweating people pored over the papers. I stood in neutral mode, breathing shallowly to both calm myself and avoid the smells. Our carefully selected and simple name wasn’t acceptable? Kibuyu what?

While I dithered, trying to understand what I could add, the man disappeared. I was terrified. Would I ever get him back? So many others awaited his attention. I had climbed up many flights of stairs between landing after landing of gloom and stink in this old, derelict building with little air or light. I’d spent agonizing minutes to find the right room on the right floor. I was desperate to finish this visit and flee. What could I add to the name?

I mulled and masticated names. At last, my mental light bulb began to glow—Kibuyu Partners. It seemed fine to me and made it even more apparent that David Bygott had a partner: me. Relieved that I’d come up with an addition to Kibuyu, I wrote the name out on a piece of paper. I stood at the desk, waiting and sweating. People frowned at me. I was taking up space, producing body heat. I went downstairs, searching for my bald man in one dim room after another. Dejected, and thoroughly apprehensive, I returned upstairs to his office, drops of sweat rolling down between my breasts and dribbling down my back. The overworked man was back in his seat.

I smiled fervently in hopes he would find my modified name acceptable. He grumbled as he read the extended title. All I could deduce from the grumble and harrumph was the name might be acceptable. He didn’t look up but scribbled on my forms—Kibuyu and Partners. I had no idea why he added the “and” between Kibuyu Partners and wasn’t about to ask. The tired-looking man raised his eyes and said, “Now, you must have your partner sign this form. It must have his signature.” He handed me the forms.

My brain sweated as I hiked back down the million or so stairs to find said partner. Neither he nor the car was where I’d left them. I was close to panic. Then I spotted David and our car far down the street, sitting under a magnificent mango tree. Relieved to find him, we discussed the new name. He signed the form. I didn’t dare to look into his face to see if he was hiding a smile or a smirk.

Back up the many flights of stairs—why are they called flights, I wondered? Terraces of Dante’s Purgatory seemed more apt. I trudged up and up. Back to the overheated room. The bald brown man accepted the signed form silently. He handed me a new form.

“Now, you must pay.”

“Where?” said I, switching my brain to low range.

He gestured out the door. “Downstairs.”

Down I went, relatively light-footed, to pay a tiny sum to a bored clerk behind a barricade. Back up the stairs to submit the form and my receipt to the overworked man in the overflowing office.

Hope rose in me as I handed him the papers, nearing the completion of this awful task. But he grumbled again. “Now, take the forms to the typists.”

“What?” I gasped, betraying too much dismay. “Typists?” I added quickly, “Where might I find the typists?”

He pointed out the door, “Downstairs.” Taking pity on me, he added, “Two flights then go right.”

I finally found the room by knocking on each of the closed doors, then trying the handle. As I slowly opened a door, I saw two women. They sat at desks free of folders or forms, just a typewriter each with a stack of paper and carbon. I looked at them, one very tubby with a round passive face, the other thin and sour-looking. Fat One wore a tight, mustard-colored polyester blouse that made me feel hotter just to look at it. Thin One had oily hair, and a newspaper spread in front of her. I coughed politely and even more politely asked for their help.

“Good morning. I wonder if one of you could kindly type this form for me? We are changing the name of our business.”

They looked at each other, then at me. “Hmmm,” I could almost hear them thinking, “Here’s a white woman begging for our attention. It is Saturday. We want to go home, not do what she wants.”

“We are busy,” announced Fat One. “We can’t type any new forms today. We close the office soon. Come back on Monday.”

“Oh no! Please, can you do it today? I could make it worth your while,” I hinted.

No response. I waited. Fat One glanced at Thin One, and both shook their heads. I knew it was hopeless.

Back I went to the bald brown man bravely fighting the paper tidal wave. “No,” he told me, “I cannot help you. I do not type. I have no typewriter. All the papers in this office have to be typed,” he paused, “by those…typists.”

I sensed just a trace of scorn in the last sentence and felt a wave of sympathy. He too must have been frustrated by the women downstairs. Putting my angst aside for a moment, I took a closer look at this man. He was an office worker, obviously not very happy about his work or where he had to do it. I thought back to the time David and I sat in the boat watching the birds in the fig trees, smelling the river, deciding about a business name in a wonderful wild habitat, our outdoor “office.”

What a difference in our lifestyles—this hard-working man, poorly paid, cooped up, living in a crowded city, and we foreigners, maybe not well paid, but living in a relatively clean and comfortable rural home. How silly, how insignificant, and how privileged we were, compared to this fellow. My distress at not getting my chore done changed into something else. Empathy? Shame? Understanding? I made a promise to myself that thereafter, I would make a much bigger effort to listen to and help the myriad supplicants who came to my own “office” in Mangola.

Since I still stood there, not saying anything, he looked up at me. I wonder what he read in my pale face with his brown eyes.

“Come back on Monday,” he said.

I shook my head automatically as though to shake away the thought. Tomorrow—Sunday—we’d hoped to be on our way home. The idea of hanging about any longer in hot, unpleasant Dar es Salaam appalled me. What could I do?

I pleaded. “Please, can’t you help me get this typing done today?”

“No,” he said definitively. “Come back Monday.”

He bowed his shiny head to his paper pile.

I bowed mine and looked at my feet, trying to fight off unwanted tears. I knew that unless I tried harder now, there would be nothing I could do but face all those stairs and floors and faces on Monday. And I feared the typists would still be too busy to deal with my typing request. I realized I probably couldn’t deal with it and would return to Mangola without our new name.

My fidgeting may have driven the bald man away because when I looked up, he’d disappeared again. I surveyed the room in desperation and decided to escape, new business name or not. As I moved towards the door, another supplicant entered the crowded room. He tried to push past me, and I backed into a stack of files on the table behind me. The folders fell in an avalanche to the floor. Mortified, I bent over to pick them up. Someone trying to help bumped into me, and I dropped them all again. Everyone turned to stare at me.

I placed the heap of mixed-up files and papers back on the table and looked around the room. All heads looked down at papers, carefully avoiding me. Now, all over Tanzania, budding businesses might remain nameless for months or years until this mess was sorted out. The economy could collapse. Hadn’t I caused enough trouble? I hated to admit defeat but I just had to go.

Tears dribbled from my eyes, sweat from my armpits, and my small pool of courage ebbed away. I didn’t want any more skirmishes with these occupants of the bureaucratic labyrinth. Midday, time to close shop. As I crept downstairs, I paused at the door of the secretaries’ room. The bald man was coming upstairs. He didn’t yet know I had trashed his office. Seeing me standing blinking back tears, he gently pushed me toward the secretaries inside the room.

In a low voice, he told me, “Leave your papers with them. They will process them when they get around to it. My office will send you a certificate with the new business name.”

I felt joy and apprehension in equal amounts. Was this a real solution? I didn’t wait to examine options or feelings. I squeezed his hands and whispered, “Thank you.” My desire to flee was so great that I did as he advised and placed my papers neatly on Fat One’s desk with a polite entreaty and expressions of appreciation for her help. What could I do but trust in whatever powers spread order through chaos and bureaucracy?

David and I left the coastal city and returned to our cooler and drier home in the near-desert of Mangola. We started to use our new business name (without the “and”) right away. However, in an overstuffed part at the back of my brain, there was a file cabinet labeled Unfinished Business. Inside lurked a scuffed file folder, Officialdumb, and in that hid the untyped form for Kibuyu (and) Partners. The whole exercise could end in a “goych”—our word for an unrealized expectation, the let-down feeling of a failed promise.

Months later, and still no name change in our post box. I typed up a standard letter imploring the business office to send us the registered name and sent it every month. No response. I dreaded another visit to hot, sticky, ugly Dar in another attempt to wrest our new business name from the offices. I knew I couldn’t return to try again. I’m not sure to this day if David was amused at all the effort that I put into changing our business name to one with the image of a gourd, a kibuyu. With his sense of humor, he would have told me, “You’re out of your gourd to go through all the trouble.”

A year after the visit to the dismal offices of Dar es Salaam, we found ourselves in Arusha town doing chores. We almost literally bumped into our seldom-seen attorney on the street. “Hello,” said this urbane, elderly Indian gentleman.

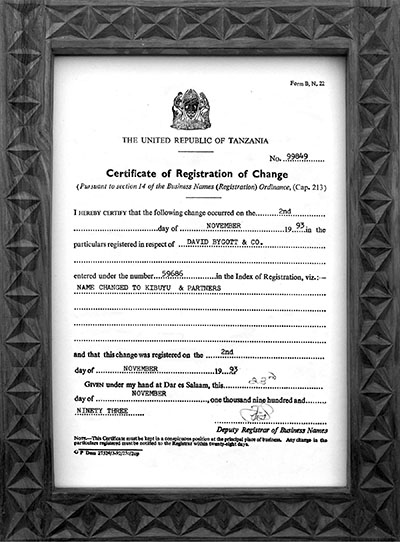

“Well, hello, Mr. Kapoor, good to see you. We haven’t seen you for months. How is the family?” Mr. Kapoor had helped us register our partnership “David Bygott & Co.” ten years earlier. Since then, we’d seen him only on rare social occasions. While we made polite conversation, he suddenly said, “Oh yes, you’d better check at my office. There is a letter for you. It’s been lying around for rather a long time.”

Oh dear, I thought immediately, what summons, or difficulty was ready to pounce on us? Taxes, fees, revocation of our business license? We grimly climbed the stairs to his office. And yes, the letter was from the Business Registration Office, certifying our duly registered name, Kibuyu & Partners. The man in the office in Dar es Salaam had kept his promise, and I would try even harder to keep mine.