Chapter 7: Mama Rama

A lesson in relationships

A young man on a bicycle wobbled to a stop under the giant acacia tree. He jumped off, propped his bike against the trunk, and started talking to the manager of the onion farm. I stood on the porch of our borrowed house trying to remember where I’d seen the lean lad. His brown-skinned legs stuck out of floppy shorts; stick-like arms protruded from his faded t-shirt. Ah yes, I remembered, he was one of Mama Ramadhani’s people.

Mama Rama was what we called her. She radiated strength and warmth, one of those women integral to a community. She knew everyone and everything that was going on. The village chairman had introduced us to her soon after we’d come to Mangola. Plump and smiling, she moved with a slow, swaying grace, swathed in skirts and kangas. Seeing her handsome face and kind, amused eyes, I intuitively knew she would be a worthwhile and vital person to get to know.

Mama Rama had a busy compound called Gorofani Junction because of its strategic position. It sat astride the main road from the lush Ngorongoro highlands into the dry Mangola lowlands. Gorofani was the first major village before the villages that were scattered like debris around the barren soda bed of Lake Eyasi.

All sorts of people stopped at Mama Rama’s place. She catered to villagers, onion lorry drivers, casual visitors, and foreigners. Her compound was a social node. People came to eat at her little café, sitting in huts or outside in the dusty compound with chickens and donkeys. Visitors from outside Mangola used her guest houses for overnight stays. Locals often just hung about being sociable or waiting for transport.

Mama Rama was middle-aged, single, with no children of her own. She told me, “Ah, husband. He went walkabout years ago.” Mama Rama seemed the titular mom for a wide array of relatives. Her extended family was diverse and fluid. Children ran around singing and playing, people came and went chatting and drinking endless cups of tea. chickens strutted in and out of houses, clucking. Ducks quacked, goats nibbled bits of grass, and donkeys heehawed while trucks on the road roared by, covering all with filmy clouds of dust. Overseeing all the confusion was Mama Rama. I liked her style, her sway, her smile.

Now I looked at the bicycle boy. Although I remembered he was from Mama Rama’s clan, his name was locked in the back of my brain. David and I were still newbies, peripheral to the village community. I wasn’t familiar with faces, let alone names. People’s names here seemed drawn out of some grab bag of words derived from family, clan, tribe, the Bible, the Quran, places, days of the week, and historical events. To my surprise, the name popped into my muddled mind—Issa.

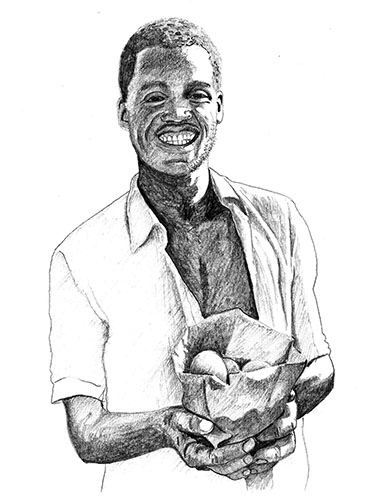

Mama Rama’s clan mostly had Arabic names. Issa was one of the few names I’d looked up: it meant salvation or protection. What might Issa be saving or protecting? He called out to me in Swahili, “Mama Simba, Mama Ramadhani amekupelekea kitu.” Mama Simba, Mama Ramadhani has sent something for you. Issa held out a soiled cloth bag. Inside were eight lovely eggs, brown and white, large and small.

I thanked him and told him to wait while I tried to find some money. But Issa shook his head. Beaming, he said, “Zawadi kutoka Mama Rama.” A gift from Mama Rama. I knew it was a gift I could not refuse.

And so, Mama Rama gave me my first lesson in trade and balances. Since her compound was on the main road in and out of Mangola, we often passed by. We soon learned to stop on our way to Karatu town to offer lifts and consult with her about supplies. Returning to Mangola, we’d stop by on our way home. From among her huts Mama Rama would appear, arms outstretched in welcome, saying, “Mama Simba, Bwana David, you must be tired having to go to town. Here, sit, have tea. Taste some of these fresh mandazi.”

Over the early years of knowing Mama Rama, she taught me reciprocity without uttering a word. Each time she sent something; I’d try to give something of equal value. She sent eggs; I sent back a bag of sugar. Mama Rama might send me a whole roasted chicken; I returned the gesture with popcorn, or sweets for the children. She’d send a bunch of bananas and I’d send back a ripe melon. Once I bought some big laying hens for her. She gave me their eggs.

Issa would ride over to bring a bottle of fresh milk. Neither David nor I drank local milk because of lactose intolerance and the dangers of brucellosis. David had contracted that disease twice from drinking unpasteurized milk. Whenever Issa brough fresh milk, I tried to refuse it or give it away. But when we started fostering three abandoned boys, the milk came is handy. In exchange for milk, I’d mend small hurts of the ever-present kids in her household. I donated bandages, gave kids shoes, brought corn for the chickens.

After four years of knowing Mama Rama while living on Mangola Plantation, David and I applied to the village for a piece of farmland of our own. The village council gave us a half-hectare of land for growing vegetables, but it was far away from our house. Mama Rama offered to exchange our plot for hers, which was conveniently located on the other side of the river from our homestead.

I made a promise to her to clear and fertilize the overused plot. To seal the deal, I offered to employ Issa. He agreed work on the plot weeding, planting, and chasing away the monkeys. Another role he would play would be the essential link between us and Mama Rama.

The garden arrangement went well. I made sure to send Issa home with some of the produce—especially the cooking bananas, papayas, melons, and tomatoes. Mama Rama would send back fried and baked goods, as well as eggs. The balance of trade continued. One day, when her old mother was very ill and needed urgently to get to Karatu hospital, Mama Rama sent over an empty jerry can.

That was an invitation to fill it up with the fuel she knew we had. I gladly gave it. Later, when the old woman died, a burial ceremony was planned. I sent over a big bag of sugar and several new mats so her many guests could have a place to sit and drink sweet tea. I kept trying to hold up my end of our continuing see-saw of give and take. It seemed almost a game, an ongoing competition of favors, both entangling and fun. I was relearning something that must have been part of human society for centuries longer than our current cash economy.

Mama Rama was unpretentious, putting on no airs for visitors of any social level, be they local farmers, politicians, researchers, foreigners, students, tourists, rich or poor. We fitted into her relaxed social nexus about as well as any of the others. She always made us feel welcome. We’d sit on a stool in the shade of one of her huts and have simple, friendly conversations with local people who would never have come to rest at our compound. Being in a neutral spot, sitting among fellow villagers gave us a sense of place, of being part of the broader social scene. Perhaps being there gave local people a way of getting to know us, too. Most villagers still did not understand why we chose to live in there. Mangola was an out-of-the way place and we lived simply with no obvious way of making money out of our situation.

We certainly were not living in Mangola to get rich. David and I were attempting to survive at a level where we could provide much of our own food and earn a living from our little publishing, artwork, and tour-guiding business. We owned no fancy equipment, no TV, no big stereo system, no generator, no expensive car. The fact that we were foreigners made us stand out enough, and we didn’t want to be even more visible.

On occasion, Mama Rama would come to our land where we were building our house by the Chemchem Stream, in my mind, our spiritual oasis. She’d usually come alone, calling out the greeting we all used, “Hodi, hodi,” an announcement of approach. We would return, “Karibu, karibu,” the welcome invitation. She would appear, swaying from side to side as she waddled slowly along the path into our compound.

She might be tracking down a goat or coming to bring yet another gift of dried fish or her doughnut-like mandazi. Whatever the reason for her arrival, I quelled the momentary pique of having my task interrupted to sit down with her. We drank tea and ate cookies while talking about the village, the people she sheltered, or what her resident researchers were doing. I always felt good about such encounters, a chance to give her back a little of the pleasure I got in sharing time, tea, news, and stories at her place.

One especially delightful researcher story she told me was about an anthropologist named Monique who came to study the livestock keeping Datoga tribe. She usually stayed at Mama Rama’s place, where she could glean local information. But staying at Mama Rama’s had its risks—security was relatively lax and Monique’s camera disappeared one day. Mama Rama was furious that anyone would take anything from one of her guests.

“I was angry, very angry,” she told me, speaking in the simple Swahili we shared. “But I knew who had probably taken the camera. There was a man who lived with maybe-wife up the hill behind me. I went there. I put my panga (machete) under my kanga and went up to his house. I told him he had better give me the camera.”

She smiled then chuckled, adding, “He looked so scared. I thought he would run away. But he went into his hut and came back with the stolen camera.”

Mama Rama had a reputation for fairness and firmness. Everyone loved her. Even so, I worried whether her minions looked after her as well as she did them. After a donkey kicked her hard in the leg, an abscess developed from the tear in her skin. I urged her to get treatment, but she refused to go to a hospital or even a local clinic. The wound was slow to heal, and she limped. There followed a long spell when Mama Rama was having what she called “fevers.” “My blood is not good,” she told me.

I was concerned she had blood poisoning from the donkey wound. She looked haggard but brushed off my attempts to get her checked. I had luck one day at the mnada, the region’s monthly livestock and supply market. On that day, the Flying Medical Service also arrived, and I was driving over to take them some tea and cookies. When I spied Mama Rama starting to limp home in the dust and heat, I stopped. “Mama Rama, you need a lift, get in.” Instead of taking her home, I took her to the thatched clinic by the airstrip, where she relented and let the doctor examine her.

His conclusion? Menopause. Mama Rama laughed when the doctor explained. I did too, having entered the post-reproductive phase myself. She and I held each other and shook with mirth. She happily accepted normal wear and tear and the final departure of monthly problems. She brightened considerably afterward and put on more weight.

Our teeter-totter relationship of giving and receiving included some bumps. Mama Rama and I had one meaningful conflict over the shamba she loaned us. Early on, as I was organizing the planting on the plot, I decided to cut back the thicket of cooking banana trees straggling around the boundary. I wanted more room for the sweet bananas and rows of vegetables.

Mama Rama came herself to complain: “Mama Simba, you remember, the shamba is mine. I have loaned it to you. You have caused a problem. I planted banana trees. The fruit is mine. You have planted different bananas. Those are yours.” I apologized profusely and tried to mollify her by giving her the papayas and sweet bananas I’d grown as well as other produce.

Some months after the banana tree incident, I heard Mama Rama calling out from across the stream. “Mama Simba, Mama Simba, nipo.” Mama Simba, I am here!” At first, it was hard to locate the booming voice. I peered through the dense screen of papyrus and saw her standing on the opposite side of the stream. I was happy to see her but worried she’d come with a complaint about the shamba. I sighed inwardly and shouted back in Swahili, “I am coming to get you.”

“How?” she shouted back.

“In our boat,” I called.

“No!” she yelled. “I am afraid of boats. I am afraid of water. I cannot swim.”

“Just wait there,” I called, already in the boat. I paddled through the papyrus tunnel to the landing on the other side. Mama Rama was a colorful figure standing there in her bright red and orange kangas, a flowered blue and white shirt with a pink paisley scarf on her head. Her hands rested on her big hips, her face with a grimace-like smile combining fear, determination, and amusement. As I pulled up, she hoisted her skirts and kangas and, without a word, stepped into the boat.

That she would trust me enough to be paddled through the papyrus and across to our dock under the fig tree made me feel proud. She grabbed the sides of the boat and tried to steady herself as she put one foot on the wooden platform. I didn’t dare try to help her because I knew this trip was a challenge, a personal test of her courage. Once across, she bravely got out of the boat, stood tall, and glided to the kitchen area where she sat down on the bench with palpable relief.

She looked at me sternly, reached into her voluminous clothing, pulling out a sack of mandazi. “I have come to see you. I was looking at the shamba. It is very healthy, very clean, full of good things. Please send Issa with some of your sweet bananas when they are ripe.”

I was enormously relieved. I made tea, and we chatted about local events, the price of onions, the girl bitten by the rabid dog, perfidious local politicians, and the bootleggers still operating in the swamp. Before she headed home, I offered to take her back to the other side in our boat.

She nodded with tight lips then said in slow Swahili, “Mama Simba, the boat ride. Yes, I liked the boat ride. But I do not want another boat ride. I will walk home from this side.”

I reckoned it was her way of telling me one courageous act was enough for one day.

On a day months later, I realized it was her birthday. I wanted to give her something special. Even though we seldom exposed our pains, problems, or gravest concerns, we were—in my opinion—good friends. We were able to give each other respect, understanding, and love without a lot of spoken words.

I chose a visual expression of these feelings, painting her home name, Hawa, on a ceramic teapot. I padded it in little sacks of tea and sugar, wrapped it up, and took it to her. Her wide smile and moist eyes as she held the pot told me she was delighted. I was too; I’d seldom seen her look so happy. She turned the teapot slowly in her big hands, admiring her name and the colorful flowers I’d painted. In her gruff voice, she said, “Asante Mama Simba. Asante sana. Asante sana, sana.” Thank you so much, thank you so much.

Through the first months of our time living near the Gorofani village, I tried to keep our trades with Mama Rama as equal as possible. But as the months passed into years, I eventually abandoned the account sheet of receiving and reciprocating. Having Mama Rama as a friend was like taking turns pushing one another on a swing. She was there for me and I for her, despite our differences. Her presence in my life significantly eased any loneliness I felt as a foreigner. I deeply valued our dynamic, balancing bond of friendship, learning give and take the Mama Rama way.