Chapter 10: Bald Rock Canyon

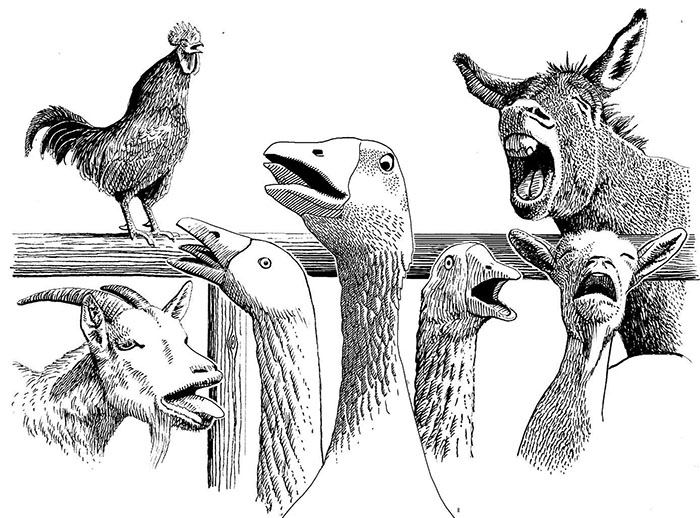

Clucking hens, honking geese, and the braying donkey invaded my dawn dreams. Where was I? Ah yes, Hedy and Andy Kala’s farm somewhere in the High Sierra Mountains of Northern California. I reached out to the chair beside the bed and pulled socks, sweater, jeans, and jacket under the covers. Struggling into all the clothes, I still shivered as I got up to put on my shoes.

The warmth of the kitchen was welcome. No one seemed around. I assumed Andy had already gone on his stage run. The cacophony of livestock outside was a vocal vote for Hedy’s whereabouts and popularity. Hedy moved through a quacking, hissing gaggle of ducks and geese on her way to the chicken house. I greeted and followed her. She instructed me to look at her hens, “I like all their colors, especially the sheen on the bantams.” Releasing the milling mob into the yard, she handed me a tin of grain to strew around.

Next was the goat barn. “And now, meet my most precious flock, the goats.” Hedy grinned as she introduced each one, then settled on a stool. While Hedy was milking her favorite goat, Mandy, I heard Hargis’ Volkswagen approaching. I hid in Mandy’s stall as Hedy blithely went out to greet him. “Oh, so sorry Bill, Jeannette couldn’t make it after all.” I peeked through the boards to see the expression on his face; would it show disappointment, concern, or relief?

He saw me before I could decide because the hay dust tickled my nose and I sneezed. Putting his face up to the boards Bill said an amused voice, “Well then, who’s this?”

I stepped out, smiling. We fell into an awkward embrace. Bill pulled me closer to him and held me tight. I smelled the wood smoke on his sweater and felt the bristle of his unshorn beard. He whispered, “I love you,” into my ear before he released me. I stepped back and looked at him, feeling a rush of emotion, happy to see him, apprehensive about being loved by him.

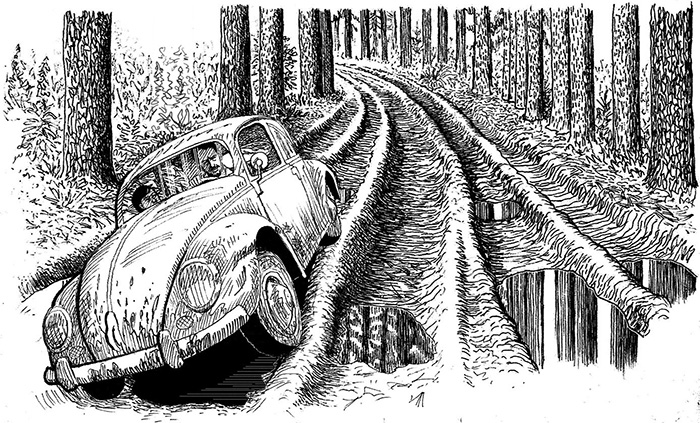

We helped Hedy carry the milk to the house. While Bill and Hedy chatted, I went to gather up my things. Hedy forced delicious coffee, scrambled eggs, and toast on us. Grateful and promising to return, we were off with a bag of supplies, including fresh eggs and goats’ milk. The missing rear window made it easy to find a place for my little bag among all the things crammed in the back. Bill’s beloved Hesperus, that mashed, bashed Volkswagen, roared along the driveway, the hole in its muffler making it hard to talk.

The Hesperus trotted like one of Hedy’s goats over the old logging roads. The load of gear clanked and bonged as we bounced over rocks and ditches. We scraped over a high hump between two deep ruts. Hargis wriggled Hesperus around till one wheel was on top of the hump, the other in a rut. I was pushed into the door with an “oomph!” of protest. Bill couldn’t resist giving me a lesson in bush driving. As we tilted into or straddled the ruts, he said, “Any good driver on dirt roads should always put a wheel on the hump in the middle. If everyone did, the hump would flatten, and cars wouldn’t high crown.” I duly took note, and I drive that way to this day.

Soon the road straightened out and the sky unrolled overhead. Bill stopped, wound down the window, and waved his arm at the curving sweeps of granite. “That’s the top of Bald Rock’s head. This spot is locally famous. The Maidu Indians lived here. They left their acorn and corn grinding holes in the rock. I’ll show you on our way out, or next time you come.” I did want to explore Bald Rock’s head with Bill, but wasn’t sure if I liked him assuming I’d return.

We drove on through stands of tall trees. Finally, we came to an eroded track leading off to a grove of what I knew were ponderosa pines. The shadows of the trees covered us as we came to rest on a carpet of pine needles. All around were the remains left by careless miners: a torn-apart car, rusty machine parts, piles of yellowed newspapers, cans, bottles, boxes, boards, barrels, and dirty socks. Bill unpacked his lanky frame from the car, stood, and stretched. I clambered out and scanned around. He saw me looking at all the debris and said wryly, “Miners aren’t known for neatness.”

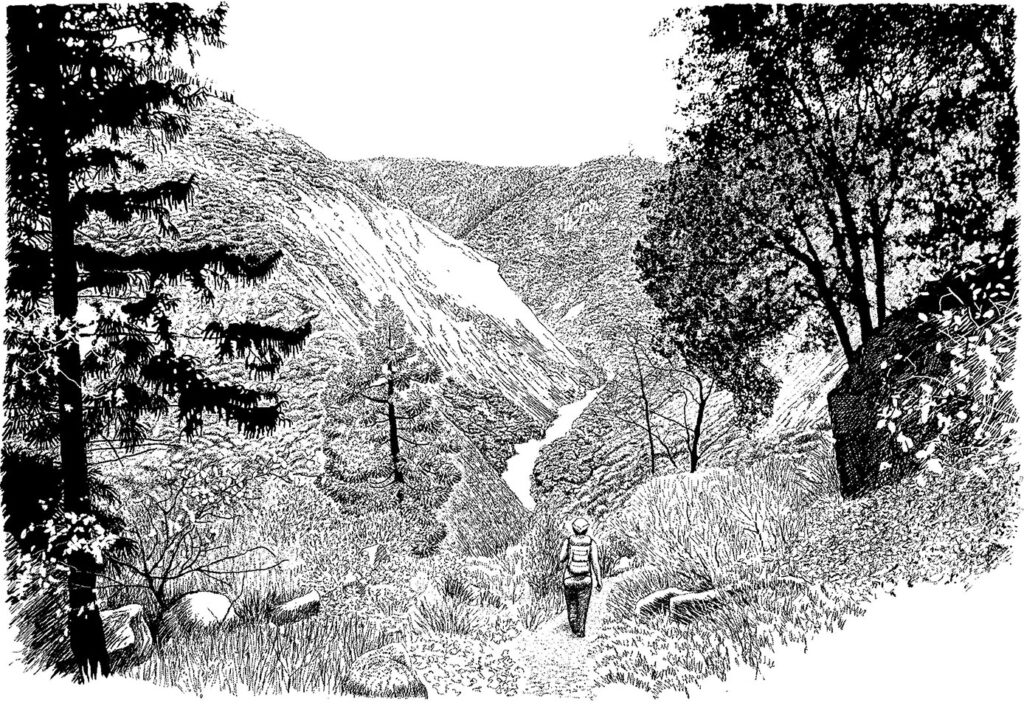

Long-crested blue jays screeched at us as we hunted for mushrooms among the manzanita bushes. We didn’t find any, and I was relieved that poison oak also seemed absent. Little nuisance flies darted at our eyes and ears, urging us to get going. We harnessed ourselves into packs and set off into the canyon along a well-worn trail. Bill kept ahead of me, muttering comments. I found it hard to hear him as the space between us increased. I called out, “Slow down please, I can’t keep up with you. What are you saying?”

He turned and swept his arm from me to beyond, “This is our easy trail. It follows an old ditch the miners used to bring water down to the workings at the bottom of the canyon. They took some care to contour the ditch properly. It makes a good trail now.”

I was glad to be on the easy trail. It gave me some time to take in my surroundings. A distant murmur of the river floated up with a cool breeze. The pine trees and chaparral plants exuded a tangy, fresh smell in the sunlight. I took a sniff of a nearby plant. Bill leaned down and fingered the leaves, saying, “This is a mountain type of ceanothus. Wild lilac. I showed you another scrubby kind in Big Sur. This one has nice flowers and smells good in the spring. Makes a tea, too, but not to my liking.”

I tried to recollect the thick clumps of ceanothus in Big Sur. California’s chaparral plants were a complex assortment. I wondered if I’d ever get them sorted out. Bill may have heard my thoughts because he said in his patronizing voice, “I’ll teach you the plants, just pay attention.” Thank you very much, I thought..

The granite dome of Bald Rock loomed over us as we switchbacked down the trail. Bill slowed down long enough for me to catch up at a turn in the trail. He pointed, saying, “Good view of the old balding fellow. Note his Mohawk haircut of trees.” I could barely see the top of the dome but was glad to stop and admire the scene. We lingered, adjusted our loads, and set off again.

Bill got bored with the easy switchbacks; he wanted to give me yet another test, or maybe just wanted to show off. Without a word, he headed off from the middle of a contour straight down into the canyon. He went loping downhill with ease and speed, sliding on his heels. I followed dutifully and carefully. Bill only paused once to turn and call out, “This is the skid trail. We bring most of the gear down this way.”

The trail was well named. Unless I kept my footing, I ended up skidding, sliding, and stumbling down the steep hillside. To keep my balance, I needed to jump and run sideways, almost dance downwards, as fast as possible. I had to trust my body to move clairvoyantly around obstacles.

The fall clutter of slick black oak leaves covered the trail. If those slippery carpets didn’t cause a hasty sit down, the treachery beneath would. Rocks, roots, crumbling granite, and holes could cause a headfirst plunge. If the underfoot treachery didn’t get you, the low and cleverly placed branches would. Being overly careful meant near paralysis, so I ran and slip-slid down.

With a final slide on my bottom over the pine needles and oak leaves, we left the terrifying skid trail. I caught my breath as I stumbled to a stop behind Bill. He turned to look at me, noting my trembling body and sweaty face. He chuckled in his amused, irritating way and beckoned me on. I reckoned I’d passed his test and gratefully followed as we resumed the last gentle switchbacks of the easy trail.

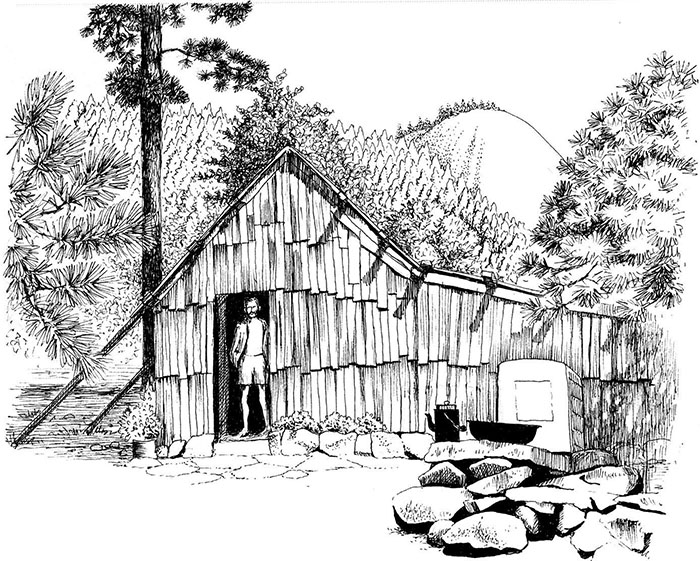

My wobbly legs grew more stable and the blood on my scratches dried as we telescoped down towards the vaguely glimpsed camp at the bottom. The roar of the river steadily increased, rich and vibrant, with moans and melodies. Bill stopped in the middle of the second switchback above the shelf of ground. I looked at the flat as he waved his long arm at the scene. Huge ponderosa and sugar pine trees dwarfed the small wooden cabin bordered by a garden plot. An old-fashioned outhouse lurked behind some oak and manzanita trees further away.

My gaze roamed to the cliffs opposite. A massive wall of granite rose up, “about twice the height of Bridal Veil Falls in Yosemite,” Bill told me. The sheer, smooth rock ended in a jagged edge at the blue autumn sky. A few trees clung to this backdrop. In contrast to the immense rugged canyon, the little open space at the bottom looked benign and welcoming.

Coming out of the trees and onto the flat, I followed Bill to a rough, wooden table under a white-barked buckeye tree. He took off his pack, then helped me get mine off, and carried the packs into the nearby cabin. It looked humble and old from the outside, but inside, it was remarkably airy and light. I looked up and noted that most of the light in the cabin came through a Plexiglas sheet. Bill noticed my gaze and said, “Yes, I added the skylight and repaired the roof each season. Built the lean-to as well.”

He’d papered the inner walls with cardboard and re-shingled the outside of the cabin, too. Bill was obviously proud of his improvements. He pointed to the stone-built fireplace, mortarless, but upright and intact. “That was built maybe a hundred years ago. I’ve done a few fix-ups. Still works, most of the time.”

“Is the cabin old?” I asked.

“Some bits might be, but most of it’s been rebuilt over the years.”

While the main light came through the skylight, the open door helped illuminate the place as well. As my eyes adapted, I focused on a well-ordered array of boxes and dishes stacked along a wooden shelf. Pots and pans hung from hooks and various sacks and bins were assembled on top of chunks of wood. A mattress wrapped in plastic hung suspended from the ceiling. Preparations against floods and rodents, I guessed.

“I always check our supplies when I come,” Bill told me as he took down the mattress and started to paw through the metal trunks and boxes. “Mike and the boys are pretty good about keeping our stores in order, but we get incompetent idiots who come down without their own supplies and make a mess of ours. And we get tourists who steal, burn, damage, and deface stuff.”

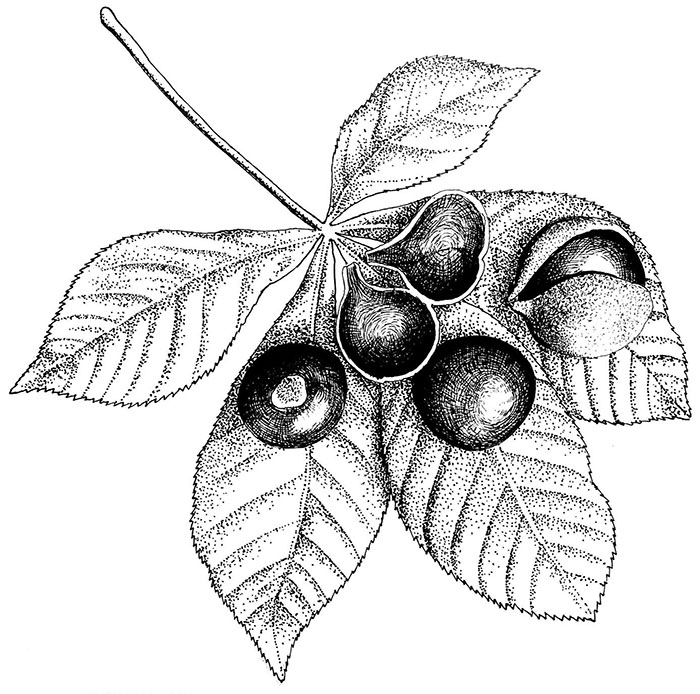

While he rummaged and grumbled around inside the cabin, I went outside. The lone camp table with two benches stood companionably under the buckeye. The naked little tree had already lost all leaves, but its deep amber “horse chestnuts” hung suggestively from the branches. Further away from the trees, some rocks were arranged in a circle, either a campfire spot or the place to cook, or both.

To the side of the campfire spot, two long shelves sagged between wooden blocks. Scattered over the rough boards were the remains of a summer’s half-hearted attempt to keep a clean camp. Plates, pots, pans, cutlery, and a big black kettle huddled together as though afraid of parting company. A variety of cups dangled from nails on the edges of the boards.

An ancient, square icebox stood nearby. I opened it and sniffed the inside. It was clean and dry, crammed full with bags of flour, oatmeal, rice, and spaghetti noodles. Near the icebox was a wooden-framed, three-tiered contraption covered with hessian sacking. Its short metal feet stood on a huge metal tray. I opened the door, wondering what it was for.

Bill came out of the cabin. He stood watching me, hands on hips, that amused smile on his face. He offered the answer to my puzzle, saying, “That’s the cool box. We put fresh vegetables and fruits in there. The hessian soaks up the water poured in the tray and the wind’s evaporative power keeps the stuff cool.” I thought that such a simple solution to cooling food in the wilds was brilliant and said so.

He smiled at my praise and said, “Let me show you my pride and joy.” He led me behind the cabin to a small gulley, with a rusty contraption tucked into the crevice. Smiling, he looked at me and said with head held high and a sweeping bow, “Meet my smoke house.”

A small door into a rusty cast iron stove was the firebox. Out the back went a pipe that led under a canvas sheet or tent. I could see that the tube directed smoke into the tent where screens were tiered inside. Bill commented, “It doesn’t look like much, but it sure does make salmon melt in your mouth. I use it to smoke deer meat too. Even use some of Hedy’s goat meat when she needs to thin her herd.”

I turned to Bill and took a good look at him. He could cook, as well as a having many other skills. He cocked an eyebrow at my stare then took me in his arms, giving me another hard hug that squeezed the air out of my lungs. I caught my breath, squirmed away, and said, “Show me more.” He gave me a tour of the garden. Ruffles of lettuce, purple eggplants, and dark green chard outlined wilting zucchini clumps and tomatoes trained up on sticks like leafy tepees. The weather had been benign, no hard freezes yet. He started a fire in the pit, waved a hand at the bench, and said, “Sit there while I make coffee.”

I sat, listening to the roar of the river and the bang of the grate being settled over the flames. Then came the clank of the old percolator style coffee pot. I realized that almost every time Bill and I had shared a meal, he’d had to have coffee, too. While waiting to go through the coffee drinking ritual, I made use of preparation time to ask questions. “Tell me something about the history of this place. I know you’ve written to me about it, but I’d like to hear more.”

“OK,” he said, “brief history lesson. Obviously, the Indians were here first. They lived hereabouts for hundreds of generations. The remnants are the Maidu. They still live up top, around Brush Creek. They’ve left their grinding stones and other clues, too. We’ve found arrowheads in the middle of the flat.”

He paused and gestured towards the distant granite face saying, “The Maidu have legends about that dome; they call it U-I-No.” I repeated his words in my head as “You-I-know.” I was puzzled by the name. Bill saw my bemused expression and drew the word U-I-No in the dust. I nodded. He continued.

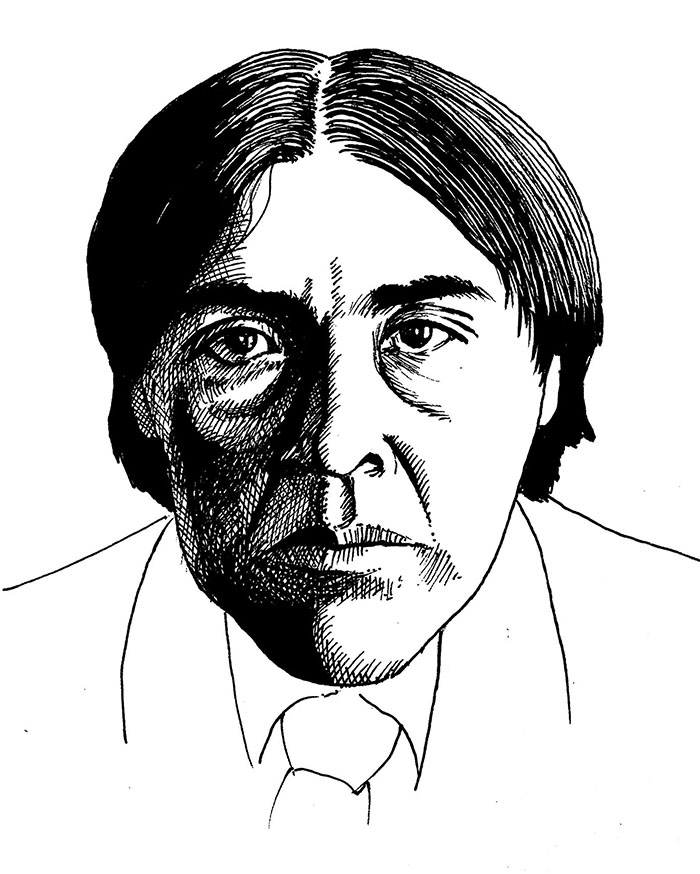

“U-I-No is the guardian of the canyon. People aren’t comfortable here. I’ve heard local Indians tell tales of red men, as well as white, who ventured into this canyon and never returned. Some people think that Ishi lived here while he was hiding out after his family and most or all of the Yahi tribe was wiped out.”

I said, “I’ve read that after many years living alone, Ishi was picked up in Oroville, trying to steal meat. That puts him in the North Fork area. We’re in the Middle Fork. Do you really think that Ishi lived here, or even saw this canyon in his lifetime?”

Bill cocked his head. “Ishi was 50 or more when he came out of the mountains. He may well have come through Bald Rock canyon. He could hunt and trap and keep out of sight. This canyon is a great place to hide.”

The story of Ishi fascinated me. I’d learned about him at Berkeley and read the book Ishi in Two Worlds. In 1911, the lone Indian was found starving outside Oroville. He was rescued from jail by anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, who then kept Ishi as a friend and living relic in the museum in San Francisco. Ishi died there. He became a symbol of the wrong done to indigenous Americans, reminding us how they were persecuted and killed off. His story made me deeply ashamed and sad.

Bill poured coffee. I sat mute at the table, thinking. How did that lone man survive? Hordes of vigilantes, miners, military, and police hunted down the natives, drove them off their land, enslaved, and killed them. The day seemed more somber, the flat lost and lonely, as I thought over what my white tribe had done to the indigenous peoples.

I gratefully took the warm coffee cup from Bill. He sat down opposite me at the table and loaded his coffee with sugar. “Do continue your history of this place,” I said, wanting to lure Bill back into a less disturbing conversation.

He sighed. “Well, after the natives, the second set of residents were the miners. They came during the gold rush. We’ve found their debris as we dug the garden. Things like square nails and hand-made turnbuckles, bits of rubber and old shovels. I even found a broken china pipe bowl, beautifully painted. I gave it to my mother, but I don’t think she appreciated it. The history of western USA never has interested her as much as the eastern.”

Hargis paused, drank his coffee, and hurried through the rest of his history lesson. He told me about the Chinese who came with and after the ‘49ers. By the end of the 1800s there wasn’t much left and the flat was an eroded mess. Then came the Great Depression during the early 1900s. A mix of miners and local Indians came back. “They reworked the whole place, sifting through all the old piles of gravel, looking for the tiniest pieces of gold.”

Bill’s cadenced voice slowed as he said, “Then, Cousteau developed the aqualung in the 1940s. Underwater dredging came along. And so, here we are.”

He got up from the table, signaling the end of his short history of Evans Bar. He took out a cigarette and lit it. Yuck. That was my cue. I stood up and headed towards the river’s roar.