Everyone loves flamingos, those bundles of pink plumes on stilts. People on our safaris always want to find and photograph them. Here in Tanzania, at Arusha National Park near Mt. Meru, there are soda lakes where flamingos cluster. Flamingos are beautiful, yes, and are also highly evolved to exploit their unique habitats – lakes full of algae and small crustaceans. They feed with beaks upside down, straining this food from greenish looking water. The chlorophyll of the algae contains carotenoids, pink or orange compounds which are deposited in flamingos’ plumage. Lesser flamingos, who feed directly on algae, are pinker than greater flamingos who eat brine shrimps. The quality of their shallow watery ‘pastures’ constantly changes, so they flap from lake to lake in the rift valley seeking the best food. We used to live on a flyway between Lake Eyasi and Lake Manyara, and often at night we’d see and hear their honking V’s passing over. These strange birds do amazing group parades, chorusing while marching, and they build crusty crater-like mud nests in the middle of desolate caustic lakes.

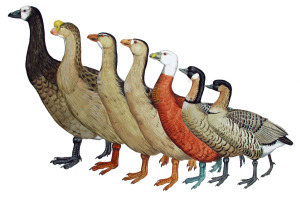

Here I want to share a fact about these fascinating birds. Researchers in 20 nations spent four years on a project to sequence the entire genomes of 48 species of birds. One of the results is that flamingos are closer relatives to pigeons and grebes than to look-alikes such as egrets and storks. Another surprise was that the chicken seems to be way back there in the genome line, closer to the original bird stock than anything except ostriches. Studies on bird evolution continue to evolve!

The Crimson Wing: Mystery of the Flamingos is a wonderful film produced in 2008 by Disney. If you missed the TV presentation maybe your library has it. This link tells you more about the film.