This month, our old friend Paul Oliver departed on his final safari. He has been part of the Tanzania tourism scene for so long that it is hard to imagine him not being there.

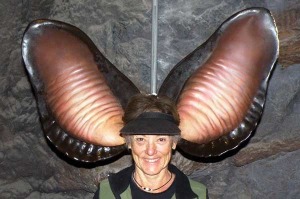

Paul first came into our lives in March 1984 as a wandering Englishman, fascinated by nature and exploring Serengeti. I was at the University of Dar-es-Salaam organizing a field course for my students to visit Serengeti and Ngorongoro. Meanwhile Jeannette was acting as temporary lion biologist at Serengeti Research Institute.

One day Paul arrived at the Lion House in his overland van. He knocked on the door and was greeted by a 5-foot high woman in a kanga. He peered down at her and asked,

“Is there a scientist around here?”

Jeannette bristled somewhat, as she has a PhD, but said “I’m a scientist. How can I help you?” “Well, there’s a snake somewhere in my van, and I need some help to get it out!”

So Jeannette marched out in her flip-flops, armed with another kanga and a glass jar, and quickly found and captured the young spitting cobra. Thus began a beautiful friendship!

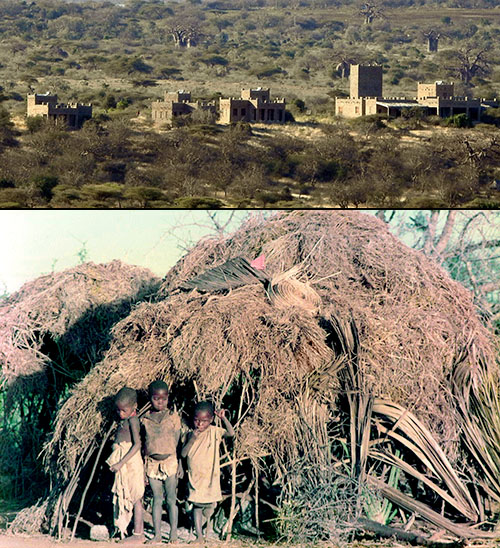

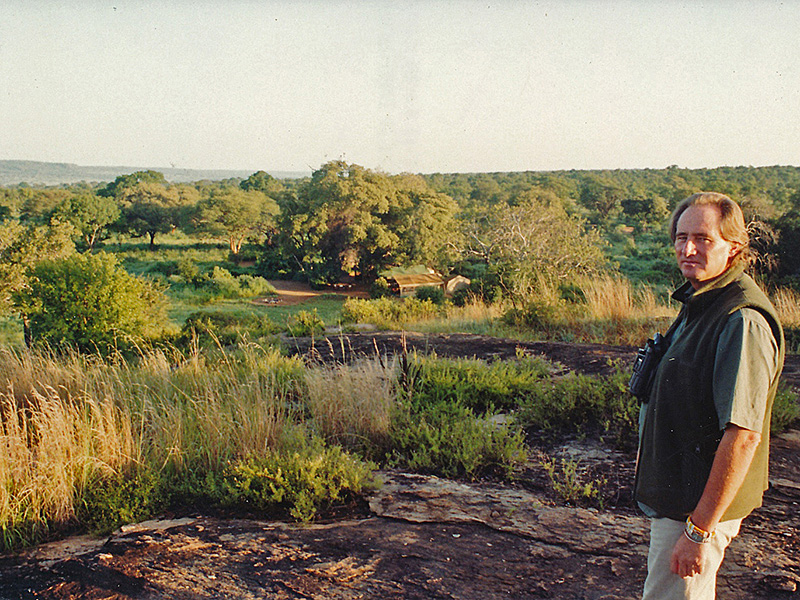

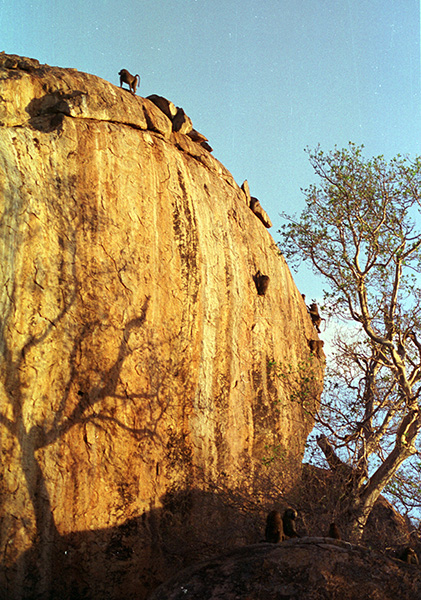

Paul soon found a niche as a driver-guide with Ngare Sero Safaris, based in Arusha. He was a quick study and became their head guide. He dreamed of having his own bush camp, and we accompanied him on exploratory trips looking for a suitable site on the border of Tarangire National Park. Eventually he established the first Oliver’s Camp at Kikoti, a beautiful location among giant rocks. From this luxurious base you could drive into the park for game-viewing, or take a walk on the wild side with Paul, or enjoy sundowners while watching baboons scale a sheer rock face to their sleeping roost. As Oliver’s Camp’s reputation grew, Tanzania National Parks encouraged Paul to move his camp to its present location within the Park. After a few years, he sold the business so that he could concentrate more on mobile camping and specialized birding tours.

During the Ngare Sero years, I did some safaris with Paul, and this diary fragment preserves a flavour of that experience:

In May 1987 Paul and I were assigned to take a family on a camping tour through Ngorongoro and southern Serengeti. We drove two Land-Rovers to Kilimanjaro Airport to meet New York lawyer Mr Goldfisch (not his real name) and his wife and two teenage daughters. The eldest daughter, we noticed, wore a neck brace.

Mr Goldfisch told us, “I hope we won’t be driving on very rough roads, because my daughter recently broke her neck”.

Paul and I looked at each other, thinking of at least 200 miles of dirt-road driving that lay beyond the end of the tarmac at Makuyuni.

“Erm, we’ll do our best to smooth out the bumps!” said Paul brightly.

The trip started well. We saw the elephants of Manyara, and toured Ngorongoro Crater. My photos show that we visited Olduvai and drove cross-country to Shifting Sands, where Paul encouraged the girls to gallop down the sand dune. Then we continued, mostly cross-country, through the wildebeest herds towards Ndutu.

About 20 miles out from Ndutu, I was driving by a small waterhole when SQUELCH! Into the mud I went. It looked like ordinary plains grass, but rain had turned the soil to goo. Stuck fast, I leaped out and ran over the rise waving to Paul to come tow me out. (No radios in those days!) Although I had royally screwed up, Paul didn’t waste time chewing me out, he just got down to work trying to solve the problem. We roped the rear end of my car to the front of his, he pulled – VROOM! VROOM! – And he got stuck too. All of us, even the mother and the daughters, set to shoveling mud, jacking up Paul’s car and putting rocks under the wheels, and we managed to get Paul out. Next we worked on my Land-rover, which was much more stuck, for another hour or so – but the tow-rope kept getting shorter each time it broke! Finally Paul decided to take the clients to the Lodge, where we’d spend the night while camp was being set up.

“I’ll send our supply truck to pull you out. Here’s a beer to keep you going!” he grinned.

With the gnus for company, I worked on the car for about 90 minutes, managing to move about a foot backwards and 3 inches deeper.

About 6pm, Paul drove back followed by Ben in his big truck, with a vast steel hawser wrapped around its front. Ben roared up behind my car and the ground trembled like jelly.

“He’ll get stuck!” I said.

“Oh no, he’s far too experienced for that!” said Paul

We hitched up the cable, Ben revved up the truck….and sank six inches into the mud!

We spent the next half hour helping Ben lengthen and deepen the ruts he was stuck in. Finally we quit and left poor Ben with the remains of our picnic lunch, to guard the two vehicles for the night. After dinner I flouted the law by driving at night from the lodge to Ben to take him some dinner in his lonely plains vigil. Springhares hopped like miniature kangaroos and ghostly freight-trains of wildebeest thundered across the road, only their eyes reflecting my lights.

Came the dawn – I was left to babysit the clients while Paul went back to the mud-wallow. He was back very quickly. Ben had woken to find about 6 lions and 30 hyenas around him! He had chased them away and unstuck the 10-ton truck all by himself and had almost got my Rover out too, which they quickly finished together.

Then Paul returned and we went game-viewing our way to camp – found a wonderful tame cheetah and followed it hunting for an hour or so. Back at camp for lunch – no truck! Paul rushed off again to search and found that the truck had died after a few miles – ruptured the water hose and bust the water pump.

Built into the truck, of course, was our camp’s water supply….

The repercussions continued. In the afternoon, while we were out for a game drive, rangers turned up festooned with AK-47s and bandoliers and pistols and demanded to search the camp, convinced that someone there had been out poaching wildlife at night! I was ordered to go straightway to the ranger post near the Lodge and explain, but it was all OK – as soon as they realized it was just me fooling around out there. I got back to camp and I told Paul with a grave face:

“It’s really bad. They’ve banned me from the Park, effective from today, and we have 24 hours to get out of here”.

He went pale with shock, until I grinned – “Just kidding!”

The safari ended well. A rescue mechanic came with the spare pump for the truck, and news that the charter to fly out the Goldfisches would shortly be coming. They were relieved to be heading back to civilization, but they were pleased with all the animals they had seen. Broken-neck Girl was no worse and seemed enlivened by her adventures, and they had enough stories, no doubt, to last for the next few decades.

After they departed, Paul and I returned to camp. We screamed and hugged each other and danced around the kitchen area, to the amusement of our staff! He broke out drinks for all, and later we drove leisurely back to Arusha.

We’ll miss you, mate.